Dominant contribution of Asgard archaea to eukaryogenesis

Database curation

For prokaryotes, 75 million sequences were curated from 47,545 fully sequenced prokaryotic genomes obtained from the NCBI GenBank (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/) in November 2023 (prok2311) and supplemented with 441,150 proteins sequences from 63 Asgard metagenomes4,5 (prok2311As), selected to represent all clades in these two publications where available. Protein sequences were either taken directly from GenBank annotations or produced by Prodigal v2.6.3 (ref. 75) trained on the set of 12 complete or chromosome-level assembled Asgard genomes. To include only those sequences that are present widely within prokaryotic families, and to minimize the possibility of post-LECA horizontal transfer from eukaryotes, soft-core pangenomes were constructed for each of our 26 curated taxonomic groups, conforming mostly to the NCBI taxonomy rank ‘class’ (see below and Extended Data Fig. 1). To construct the soft-core pangenomes, all sequences from each taxonomic group were clustered individually using mmseqs2 (ref. 37) ‘mmseqs cluster -s 7 -c 0.9 –cov-mode 0’37.

All clusters that did not contain sequences from at least 50% of all bacterial species (here defined by lowest rank taxonomic ID within the NCBI taxonomy), or 20% of eukaryotic sequences (see below), were rejected from the database. The effects of alternative pangenome definitions, such as 10%, 25%, 50% and 67% proteins per class, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1d.

The eukaryotic database was constructed starting from a curated set of 72 genomes available from the NCBI GenBank. To provide a more accurate representation of eukaryotic diversity, this dataset was supplemented with EukProt v.3 (ref. 36)—a curated database aiming to provide a sparse representation of eukaryotic biology, to create Euk72Ep containing 30.3 million sequences. As sequences included in EukProt v.3 come from a diverse range of sources, some known to contain contaminant prokaryotic sequences, the database was screened for prokaryotic contamination. This screen was carried out by first constructing candidate prokaryotic and eukaryotic HMM databases as described below and querying both databases against the eukaryotic sequence database using hhblits43. All eukaryotic sequences with a top hit alignment score from a prokaryotic HMM were removed from the database before initial clustering.

Curation of taxonomic labels

To provide a compromise between taxonomic specificity and accuracy of clade assignment, we curated a set of taxonomic labels for both Euk72Ep and Prok2311As to act as representatives. To construct this set, we started by manually assigning all species in EukProt to their closest relatives in the NCBI taxonomy. Then, each species from Prok2311As and Euk72Ep was assigned a taxonomic label corresponding to their ‘Class’ rank (for example, Alphaproteobacteria, Thermococci, Mammalia) based on the NCBI Taxonomy of November 2023 using tools from the ete3 v.3.1.3. toolkit76 as well as custom scripts. For species without a corresponding ‘Class’ rank, the closest relevant rank was assigned manually. This procedure yielded an initial list of 317 unique taxonomic class identifiers.

As the rank ‘Class’ does not partition biological diversity evenly, identifiers were further mapped manually to a curated set of 45 eukaryotic and 26 prokaryotic taxonomic superclasses, each present in the NCBI taxonomy (for example, Metazoa, Streptophyta, TACK archaea; Extended Data Fig. 1. Due to the partially unresolved taxonomic relationship within Asgard archaea, all candidate Asgard sequences from Prok2311 or from refs. 6,7 were assigned to the class label ‘Asgard’. Following the recent reclassification of Deltaproteobacteria into Myxococcota, Desulfobacteriota, Bdellovibrionota and SAR324 species that could not be mapped into either of these clades using existing taxonomic annotation were classified as Deltaproteobacteria (0.025% of total data).

Sequence clustering and profile database generation

To transform Euk72Ep and Prok2311As into profile databases suitable for sensitive HMM–HMM searches, we implemented an unsupervised, cascaded sequence-profile clustering pipeline using the tools available in the mmseqs2 software suite37. In brief, each sequence database was initially clustered at 90% sequence identity and 80% pairwise coverage using ‘mmseqs linclust’ and cluster representatives were chosen using ‘mmseqs result2repseq’. This procedure provides a non-redundant set of 6.3 million prokaryotic and 25.1 million eukaryotic sequences for further analysis. The non-redundant sequences are further collapsed into a set of initial profiles and consensus sequence pairs using ‘mmseqs cluster’, ‘mmseqs result2profile’ and ‘mmseqs profile2consensus’. All consensus sequences are queried against their profiles using ‘mmseqs search’ and results clustered using ‘mmseqs clust’. Clusters are mapped to their original non-redundant sequences using ‘mmseqs mergeclusters’ and profiles and consensus sequences are constructed once again.

To grow clusters based on their sequence-profile alignments, this procedure of ‘mmseqs profile2consensus – mmseqs search – mmseqs clust – mmseqs result2profile’ is iterated until cluster sizes converge. An 80% pairwise coverage is maintained throughout all steps of the cascaded clustering protocol to avoid homologous overextension. The final clustered databases contain 14.1 million and 91,000 clusters for Euk72Ep and Prok2311As, respectively.

To transform the unsupervised clusters into a set of HMM profiles, we used a mixed MSA construction strategy coupled with automatic data reduction to create accurate alignments for a wide diversity of cluster sizes and sequence diversities. To construct HMMs, all non-singleton sequence clusters are first aligned using FAMSA v.2.0.1 (ref. 77) to produce an initial alignment. Using the initial alignment, we then reduce the sequence space by calculating an approximate tree using FastTree v.2.1.1. using ‘FastTree -gamma’78, remove long branch outliers as described in ‘EPOC tree construction and processing’ and iteratively removing the closest pairwise leaves using ete3 (ref. 76), keeping the leaf closest to the root, until the desired sequence set size is reached. For profile generation, we retain no more than 300 sequences for both Prok2311As and Euk72Ep. This reduced sequence set is then realigned with muscle5 v.5.1.linux64 (ref.

42) using ‘muscle -diversified’ with five replicates, and the maximum column confidence alignment is extracted using ‘muscle -maxcc’. This alignment is then trimmed to keep columns with more than 0.2 bits of Shannon information defined as the difference of log2(20) and the Shannon entropy of the column amino acid distribution. This process of data reduction/alignment/trimming is referred to as ‘prune-and-align’ and used later for downstream analysis. Trimmed alignments are turned into an HMM database using HH-suite with ‘hhconsensus -M 50’, hhmake and ‘cstranslate -f -x 0.3 -c 4 -I a3m’. The final HH-suite databases contained 480,000 and 1.6 million profiles for prokaryotes and eukaryotes, respectively.

Cluster annealing

As the initial mmseqs2 based clustering was carried out in an unsupervised manner, we considered it necessary to ensure that the results were not contingent on our unsupervised partitioning of the data. To this end, a further cluster annealing step was developed which aims to redefine clusters based on the notion of clades as well separated monophyletic groups on phylogenetic trees, rather directly by sequence similarity and coverage. Starting with the existing clustered databases Euk72Ep and Prok2311As, HMM profiles were calculated for each non-singleton cluster and all versus all HMM–HMM searches were performed using HHblits v.3.3.0 (HHblits -n 1 -p 80), retaining hits with at least 80% HHblits probability and 50% pairwise profile coverage. The resulting hits were then clustered using greedy set clustering, as described in mmseqs2, implemented in Python.

These superclusters represent our limit of detection for sequence-based methods, but might involve overclustering, possibly merging several similar gene families into one set. To mitigate the potential effect of such overclustering, cluster partitioning was performed based on phylogenetic tree analysis.

To this end, the supercluster sizes were first reduced using the ‘prune-and-align’ approach described above, after which a master tree was constructed using FastTree -gamma. Given the resulting set of trees, we sought to identify well separated monophyletic sets of leaves, the presence of which would warrant partitioning of the respective superclusters. To perform this tree partitioning in an unsupervised manner, the all-versus-all pairwise leaf distances were calculated as a square distance matrix and embedded into two dimensions using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection v.0.5.3 (n_neighbors=50, min_dist=0.3, distance=‘euclidean’)79. This embedding was clustered using HDBSCAN as implemented in scikit-learn v.1.3.0 with default parameters80. We explicitly allow single cluster partitions to ensure that trees with uniform distributions of pairwise branch lengths remain as single clusters.

Mapping clusters back to the phylogenetic trees showed that uniform manifold approximation and projection embedded HDBSCAN clusters were well separated in the original trees (Extended Data Fig. 3a). These annealed clades were used in downstream processing, representing a stricter definition of EPOCS than the initial cascaded mmseqs2 clusters. The annealing process redistributed sequences from the 1.6 million eukaryotic clusters into 1.5 million annealed clusters and from 480,000 prokaryotic clusters into 280,000 annealed clusters, highlighting the already dense representation of initial mmseqs2 clusters. Because the embeddings were done per tree, the partitioning into subsets is independent of branch lengths and relies merely on the internal distribution of branch lengths and the sequence diversity within each tree, rather than pre-defined values of tree distances. Thus, well-formed subclades could be identified in sequence sets independent of internal diversity, an essential feature when applying this procedure across our global scope.

Search for prokaryotic homologues of eukaryotic proteins

Given that clade-specific protein families were not of direct relevance to this study, we reduced the search space by excluding HMM profiles from eukaryotic clusters with fewer than ten sequences and a lowest common ancestor with a taxonomic rank below ‘Superkingdom’ as calculated by ‘mmseqs lca’. This requires a sequence cluster to contain at least two sequences from different kingdoms, as defined by the NCBI taxonomy (for example, Amoebozoa and Haptista, or Viridiplantae and Opisthokonta), retaining 142,000 profiles of conserved eukaryotic proteins. To associate eukaryotic sequence clusters with homologous prokaryotic clusters, we queried the Euk72Ep HMM database against all Prok2311As HMM profiles using a single iteration of HHBlits v.3.3.0 as ‘HHblits -n 1 -p 80’ and retaining the hits with at least 80% HHblits probability and 80% pairwise profile length. These filters resulted in a total of 20,700 accepted eukaryotic query profiles targeting a total of 8,300 unique prokaryotic profiles.

These clusters contained a total of 5.7 million and 1.9 million sequences.

EPOC MSA construction

Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent steps were carried out using custom Python v.3.9 scripts, with taxonomy and tree parsing carried out using ete3 (ref. 76). All sequences from a eukaryotic cluster with at least ten sequences and a lowest common ancestor at the rank of ‘Superkingdom’ (NCBI taxonomy), together with all members of the homologous prokaryotic clusters identified in the HMM–HMM search with at least 80% probability and pairwise sequence coverage, forms an EPOC. As EPOCs varied in size by more than five orders of magnitude (10 to 100,000 sequences), robust data subsampling is necessary for accurate downstream MSA generation and tree construction. We used a variant of the ‘prune-and-align’ strategy described above for profile generation taking into account the taxonomic distribution of the constituent sequences.

Rather than iteratively pruning the closest leaves pairwise, we first label each leaf with its corresponding taxonomic label and only prune monophyletic groups, maintaining a count of all pruned leaves per clade. If the procedure fails to reach the target leaf number before converging, all leaves are ordered by the number of pruned relatives and leaves with the lowest number of relatives deleted (retaining the largest monophyletic groups) until the target size is reached. The result approximates a maximum diversity representation, preferentially pruning isolated singleton clades. Using this modified protocol, eukaryotic and prokaryotic sequences are cropped to a maximum of 30 and 70 sequences, respectively. Each EPOC therefore consists of a maximum of 100 representative sequences. All EPOCs are aligned using ‘muscle -diversified’ with five replicates, and the maximum confidence alignment is extracted using the –maxcc argument.

This alignment is then trimmed to keep columns with more than 0.15 bits of Shannon information content for tree reconstruction.

EPOC tree construction and processing

From the pruned and trimmed alignment, we created a maximum likelihood tree using IQtree2 v.2.3.5. ‘IQtree2 -B 1000 -bnni -m MFP -mset LG,Q.pfam –cmin 4 –cmax 12’ with model parameters estimated by model finder plus46. Candidate models and rate category search ranges were selected based on a test set of 200 randomly chosen EPOCs from the filtered core set analysed with full model parameter evaluation by Model finder46 and ten tree replicates. The LG and Q.pfam models and rate category ranges were chosen as they consistently produced the highest ranking log-likelihoods for a random sample of 200 EPOCs run with full model estimation in IQtree.

As the master trees are built from sequences obtained through sensitive cascaded sequence-profile clustering, we would in rare cases observe long-stemmed clade outliers in addition to more common long stem leaf outliers. To assess and remove such erroneous data, we first estimated the log-normal distribution of all stem lengths using scipy.stats v.1.11.1 and excluded any stems outside the 0–99.5% probability point function interval. This simultaneously removes long terminal leaf branches as well as highly diverged clades. In rare cases where this pruning would remove either the entire eukaryotic clade or more than 30% of all leaves, the EPOC was discarded (387 EPOCs). The resulting trees were then re-rooted using a weighted midpoint approach so that the sum of all branch stem lengths on either side of the root was equal. For clarity, no trees in our current study have been ‘phylogenetically rooted’ in the biological sense.

All references to the ‘root’ refer to the origin of the data structure, not the biological concept.

To assign taxonomic clades, all leaf nodes were assigned taxonomic labels from our curated set and monophyletic clades were collapsed, taking as the representative the lowest branching leaf. We found that assigning clades purely based on a monophyletic definition of taxonomic purity severely hampered the analysis as leaves can be taxonomically incongruous with their neighbours. This effect most likely stems from cases of locally erroneous tree topology or local HGT, but severely complicates the downstream analysis. We therefore adopted the notion of a ‘soft LCA’ representing the root of a close-to-monophyletic clade. To greedily rank all the best ‘soft LCAs’, for each taxonomic label, the tree was traversed from each monophyletic clade root to the tree root, calculating a score for each internal node:

$$({rm{Number}},{rm{of}},{rm{leaves}},{rm{with}},{rm{label}},{rm{X}},{rm{in}},{rm{clade}}/{rm{clade}},{rm{size}})times ({rm{Number}},{rm{of}},{rm{leaves}},{rm{with}},{rm{label}},{rm{X}},{rm{in}},{rm{clade}}/{rm{total}},{rm{number}},{rm{of}},{rm{label}},{rm{X}})$$

This metric balances taxonomic ‘purity’ and ‘scope’ for each possible clade of label X. All such nodes are then ordered by this score. Because this score is sensitive to the total number of taxonomic labels in an EPOC, it was not used as a filtering criterion at any point in the analysis, yet is present in the metadata, mentioned here for completeness. To avoid overinterpreting small clades, clades were considered valid if they represented at least three sequences with clade purity more than 0.8 for prokaryotes, and at least five sequences with purity more than 0.8 for eukaryotes. Trees that fail to identify either any eukaryotic or any prokaryotic clades under these constraints, derived primarily from small EPOCs, are discarded (411 EPOCs). Trees with more than three valid eukaryotic clades were considered to show high paraphyly and likewise discarded (781 EPOCs).

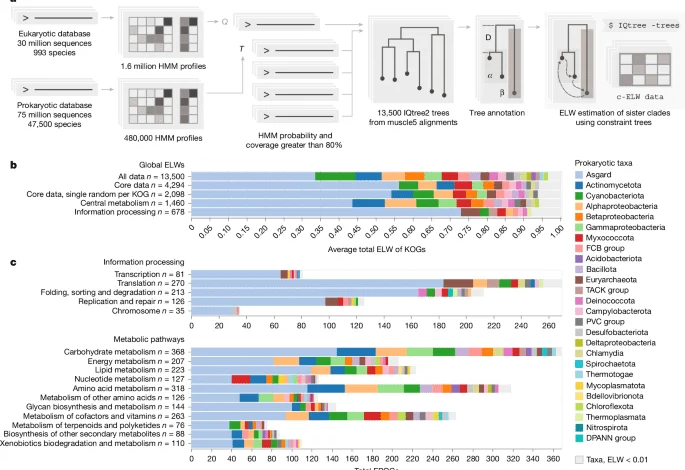

Evolutionary hypothesis testing using constraint trees

To assess the relative probabilities of each sampled prokaryotic clades to represent the eukaryotic sister clade, we used evolutionary hypothesis testing using constraint trees as implemented in IQtree2 (ref. 46). For each EPOC and for each detected eukaryotic clade, we generated a set of constraint trees, one for each possible prokaryotic sister. Each constraint tree had three defined clades enforced throughout tree calculations: (1) the eukaryotic group as defined by all sequences below the eukaryotic LCA, (2) one of the prokaryotic sister groups and (3) all other prokaryotic leaves. We then construct a set of local trees from slices of the original MSA using IQtree2, forcing the constraint tree topology using ‘iqtree2 -g’, using the same evolutionary model as the original, unconstrained ‘master tree’.

The set of constrained trees is then ranked using ‘iqtree2 -z’ calculating the relative model assignment confidence for each of the constrained topologies and resulting test metrics are saved for downstream analysis. As the number of trees to evaluate scales by the number of eukaryotic clades multiplied by the number of prokaryotic clades, we limit the sampling to a maximum of three clades per tree for eukaryotes, discarding rare cases of high eukaryotic paraphyly, and only consider the 12 closest prokaryotic clades to each individual eukaryotic clade, based on their topological distance calculated as the number of non-root tree bifurcations from one node to another. The procedure results in an ELW44 for each of the evaluated model trees, here taken as being analogous to model selection confidence that an evaluated prokaryotic clade is the most significant sister to a eukaryotic clade.

EPOC annotation

To functionally annotate protein families within EPOCs, we generated profiles based on protein sequences in KEGG release v.110 (ref. 45). For each KOG, we extracted KEGG metadata including KEGG pathways and BRITE labels through KEGG’s API. At the time of parsing (January 2024), KEGG contained 26,695 KOGs. Due to KEGG API constraints, protein sequences in KEGG were extracted from Uniprot, first by mapping KEGG proteins to Uniprot IDs using Uniprot’s ID mapping service (https://www.uniprot.org/id-mapping), then by extracting the sequences for these Uniprot IDs corresponding to each KOG81.

For each KOG, we generated HMM profiles using the prune-and-align pipeline. To increase specificity of labelling, we partitioned those KOGs, which encompass both prokaryotic and eukaryotic sequences, into separate taxonomic groups and sequence alignments were generated separately for prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Each eukaryotic HMM profile forming the basis for a EPOC was queried against our KEGG profile database using ‘HHblits -n 3 -p 80’. Results were subsequently filtered to a pairwise profile coverage of 0.7 using custom scripts. As a result, 12,600 of the 13,500 EPOCs could be annotated by at least one KOG profile at 80% probability and 70% pairwise coverage. The highest probability hits were used for annotation.

Data filtering and removal of cases of possible late HGT

Unless otherwise stated, all data are interpreted from the core set of EPOCs meeting the following criteria: (1) the eukaryotic constituent cluster profile identifies at least one target profile in our KEGG profile database at a probability of 80% and 70% coverage; (2) the eukaryotic clades include more than five distinct taxonomic labels, at least one from Amorphea and one from Diaphoretickes, encompassing the LECA and (3) only prokaryotic sister clades with 0.4 < ELW < 0.99 were considered reliable and were included in the analysis. We note the independence on aELW values on the number of eukaryotic clades chosen as a cutoff as shown in Extended Data Fig. 10a. Cases of ELW ≥ 0.99 were not considered as these are found to be disproportionately eukaryotic-like, often branching from within a broader eukaryotic clade, and thus likely derived from late horizontal transfer post LECA. Due to the presence of such high ELW values within alphaproteobacterial associations with Oxidative phosphorylation, in this case, as an exception, ELW values of 1 were included.

Taxonomy remapping and EPOC construction under GTDB taxonomy

To ensure that the results were robust to taxonomy, the prok2311 database was reformatted under the GTDB taxonomy (v.220) at the level of ‘phyla’49. For taxonomic mapping, first, genomes present in both prok2311 and GTDB were annotated directly with the GTDB taxonomy. For the remaining genomes, taxonomy was assigned through consensus voting by using the set of GTDB marker genes, searching against our data using ‘mmseqs search -s 7 -c 0.5 -e 1e-10’. A phyla level taxonomic label was assigned to each genome based on the largest number of total hits. Genomes without significant hits to GTDB marker genes were discarded for the purpose of this analysis (0.92% of all data). This procedure mapped the prok2311 data to 96 GTDB phyla that were used as taxonomic assignment for EPOC calculations as described above. All additional Asgard data taken from ref. 8 were directly assigned as Asgardarchaeota.

Data visualization and plotting

All plots were prepared using Python v3.9 and pandas v.2.0.3 with Altair v.4.2.2. Layout, annotation and vector editing was done using Inkscape v.1.1.1. All statistical tests were carried out using scipy.stats v.1.11.1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

تنويه من موقعنا

تم جلب هذا المحتوى بشكل آلي من المصدر:

yalebnan.org

بتاريخ: 2026-01-15 00:16:00.

الآراء والمعلومات الواردة في هذا المقال لا تعبر بالضرورة عن رأي موقعنا والمسؤولية الكاملة تقع على عاتق المصدر الأصلي.

ملاحظة: قد يتم استخدام الترجمة الآلية في بعض الأحيان لتوفير هذا المحتوى.